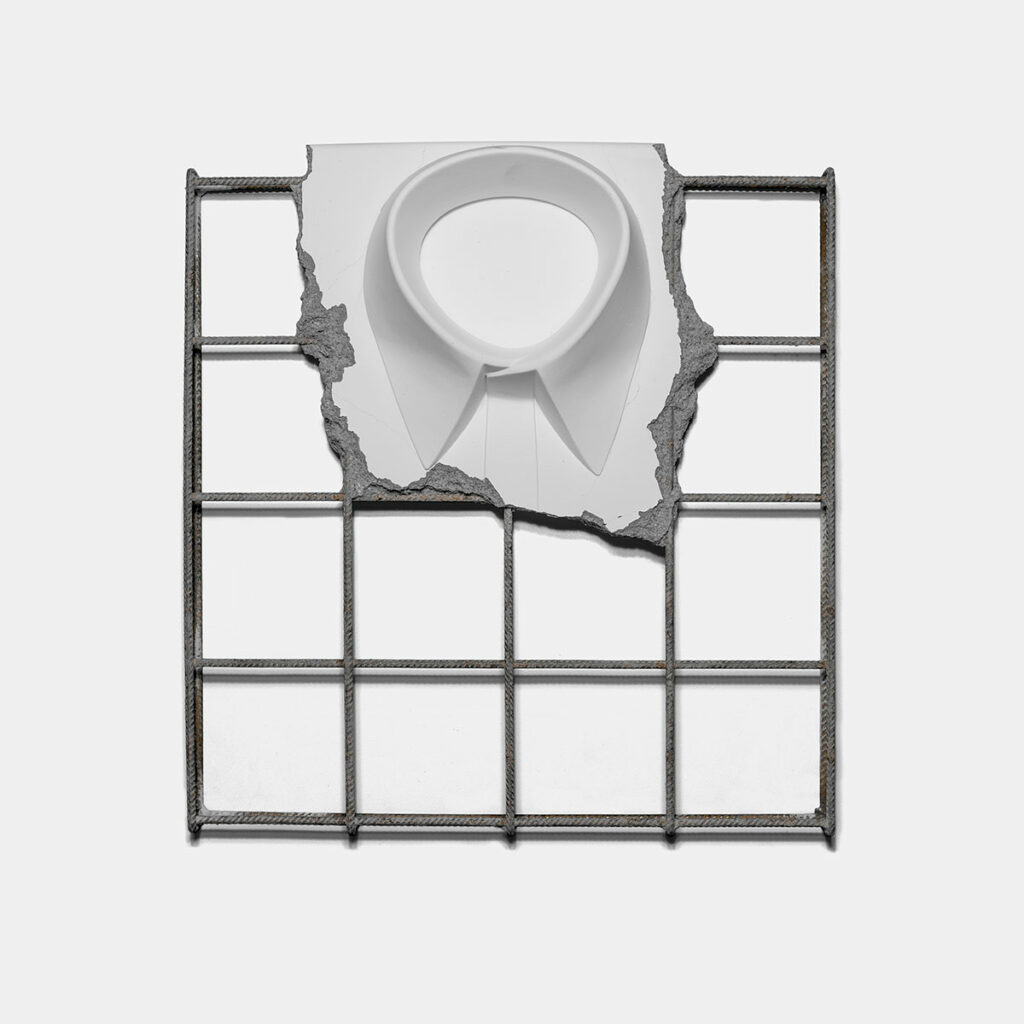

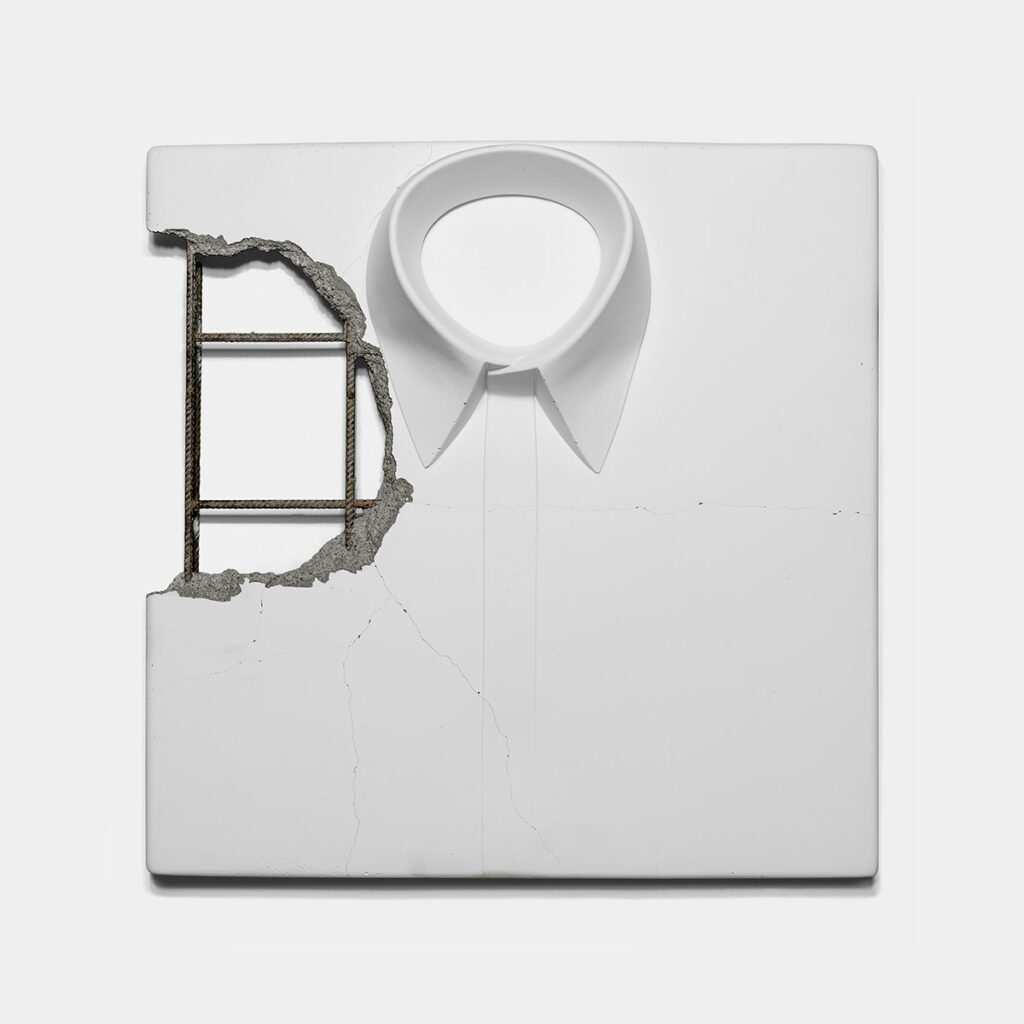

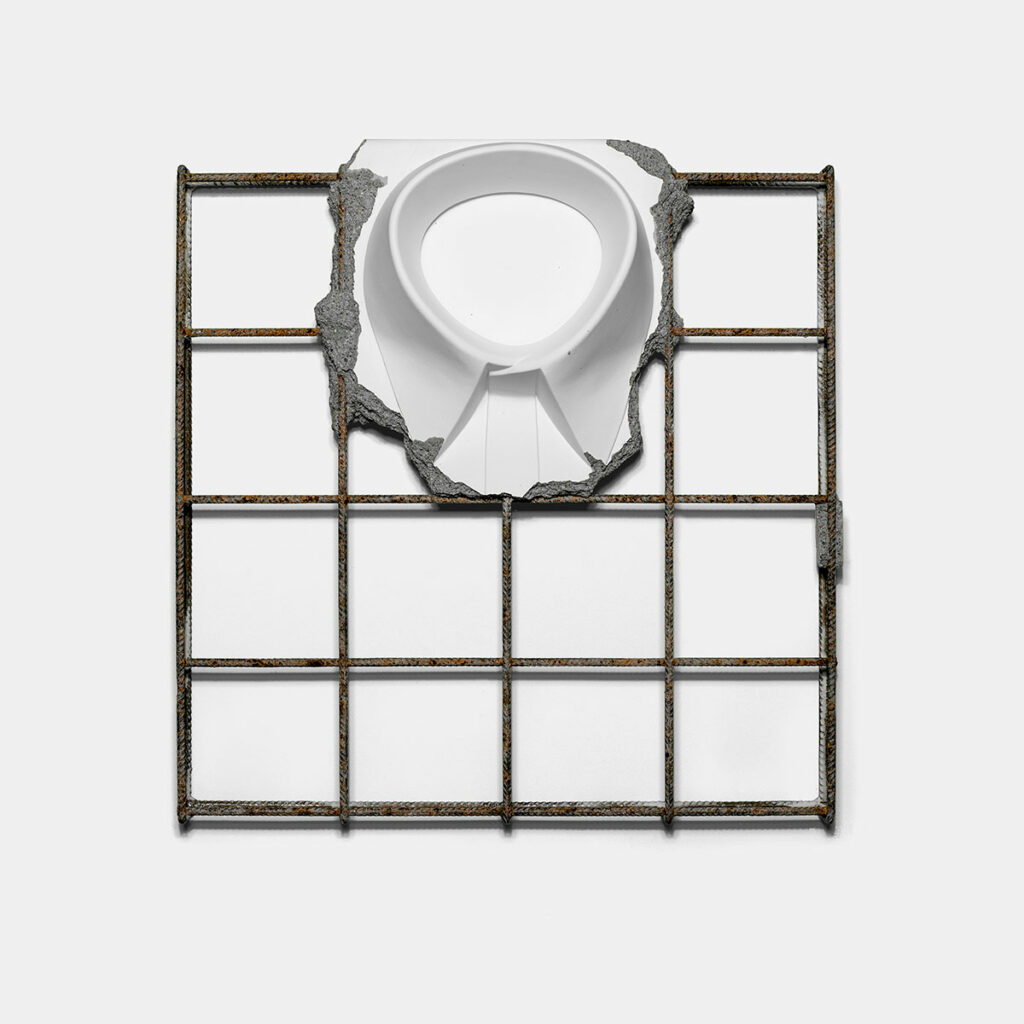

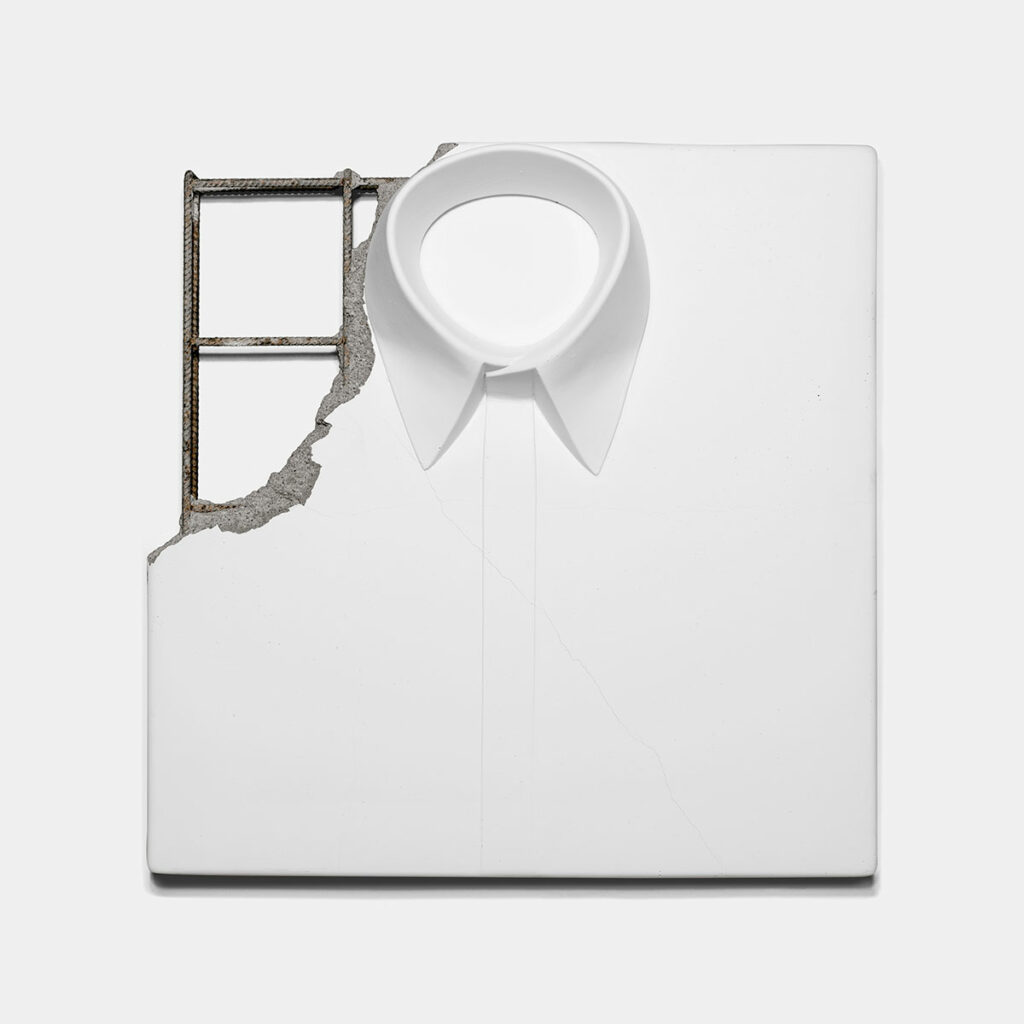

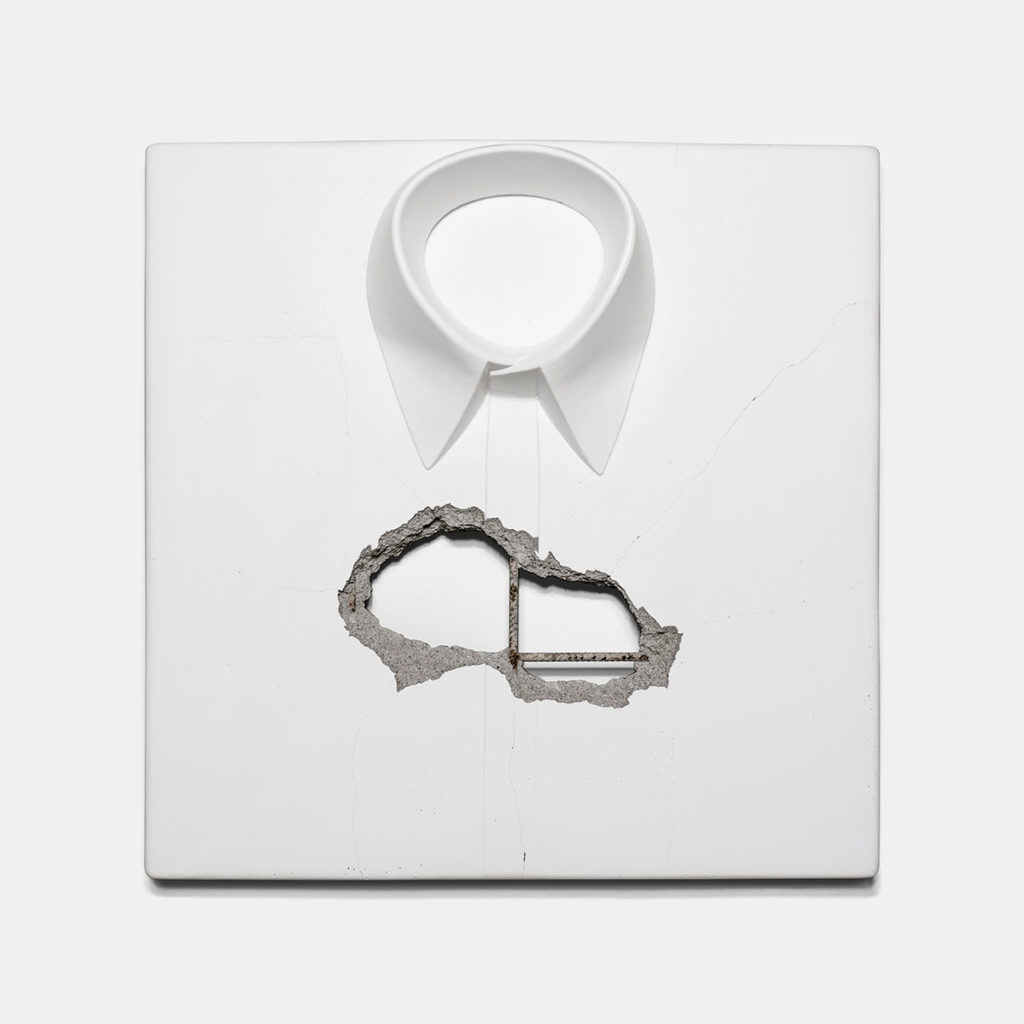

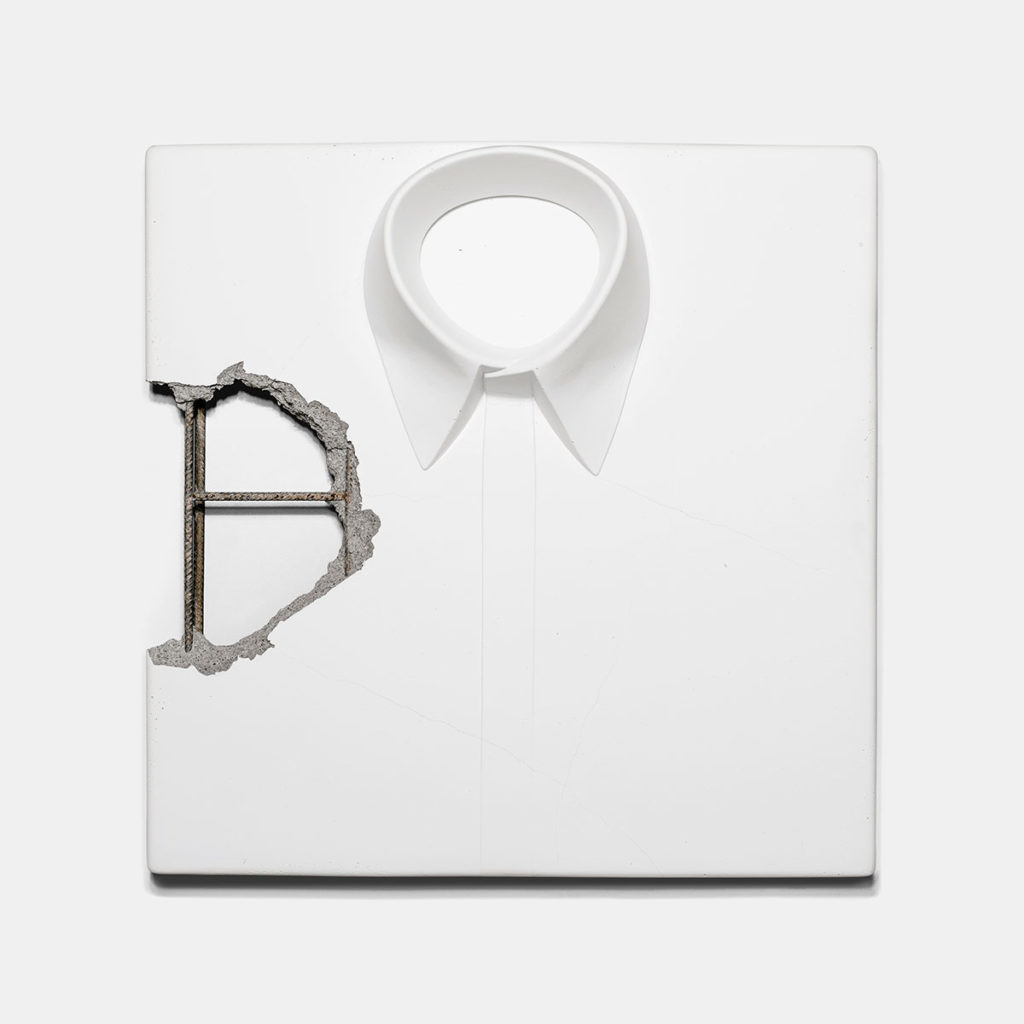

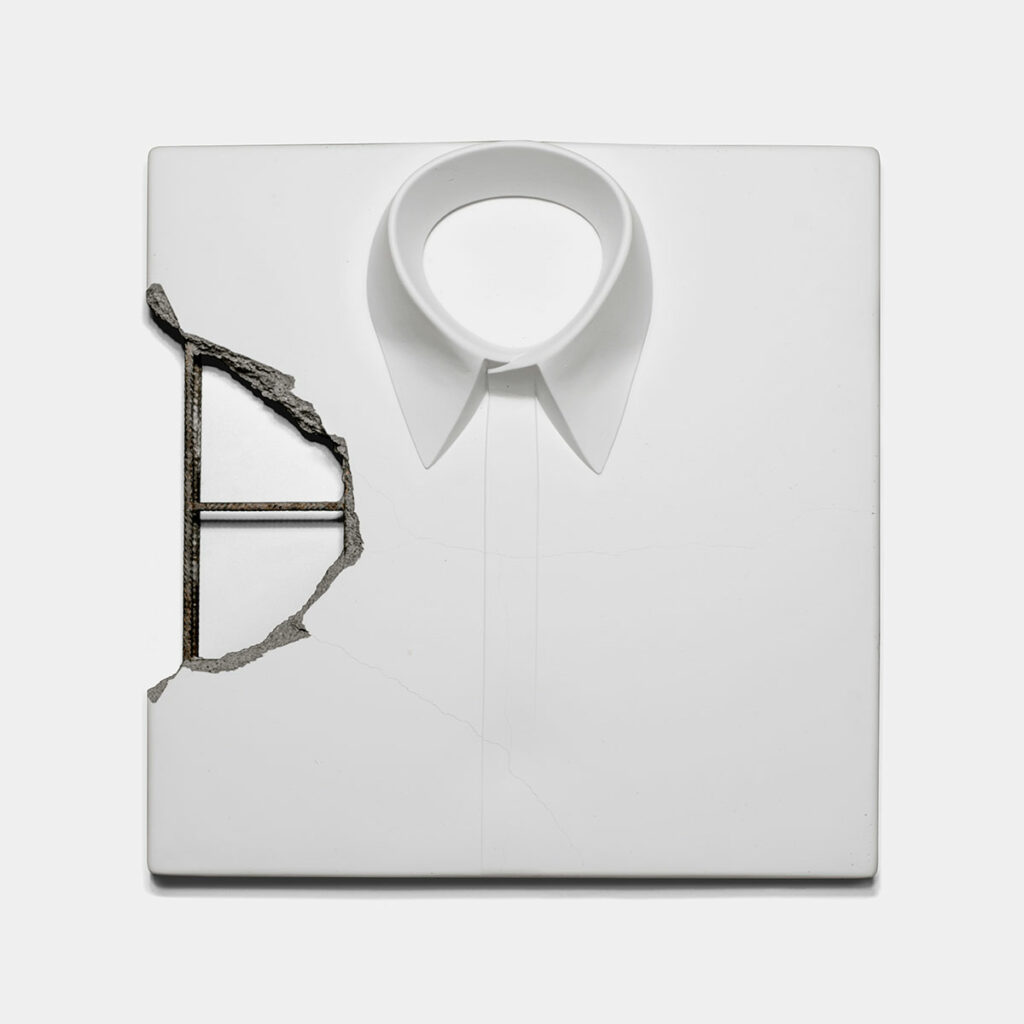

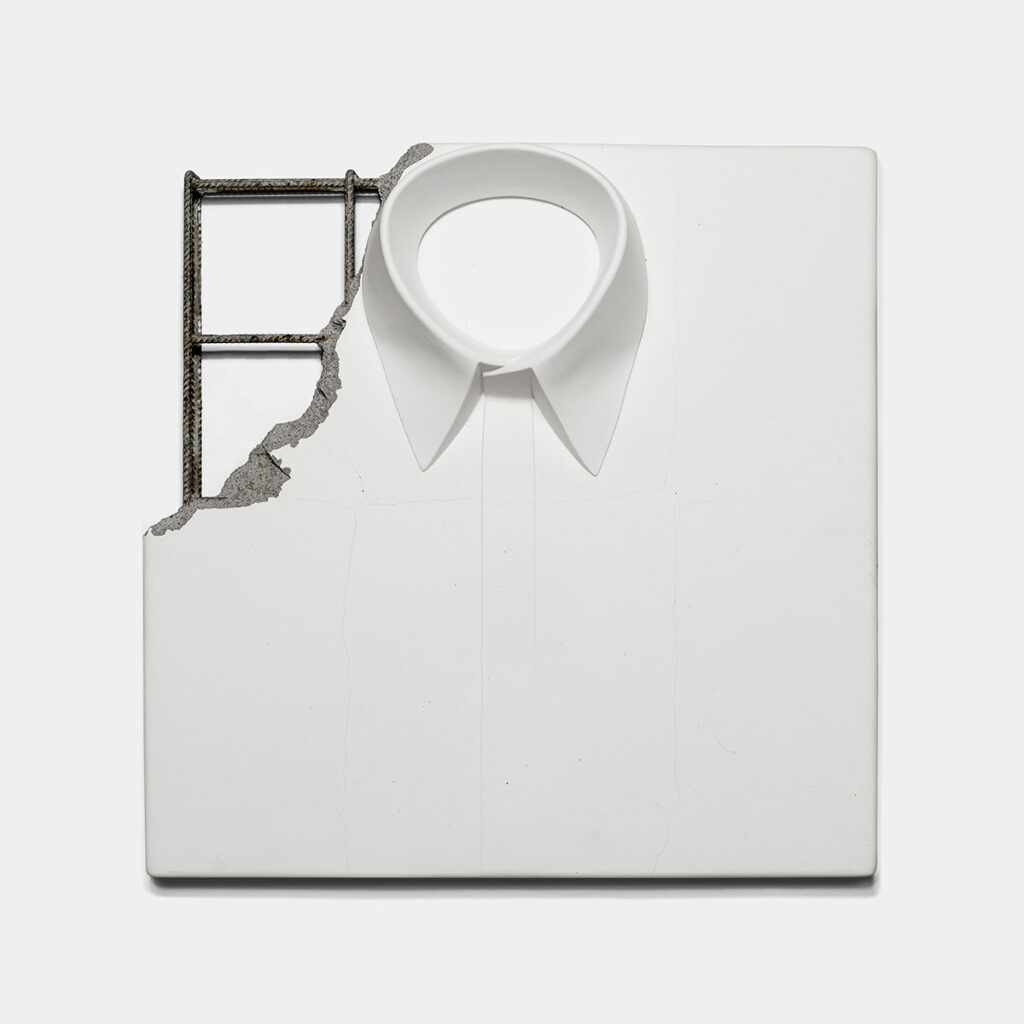

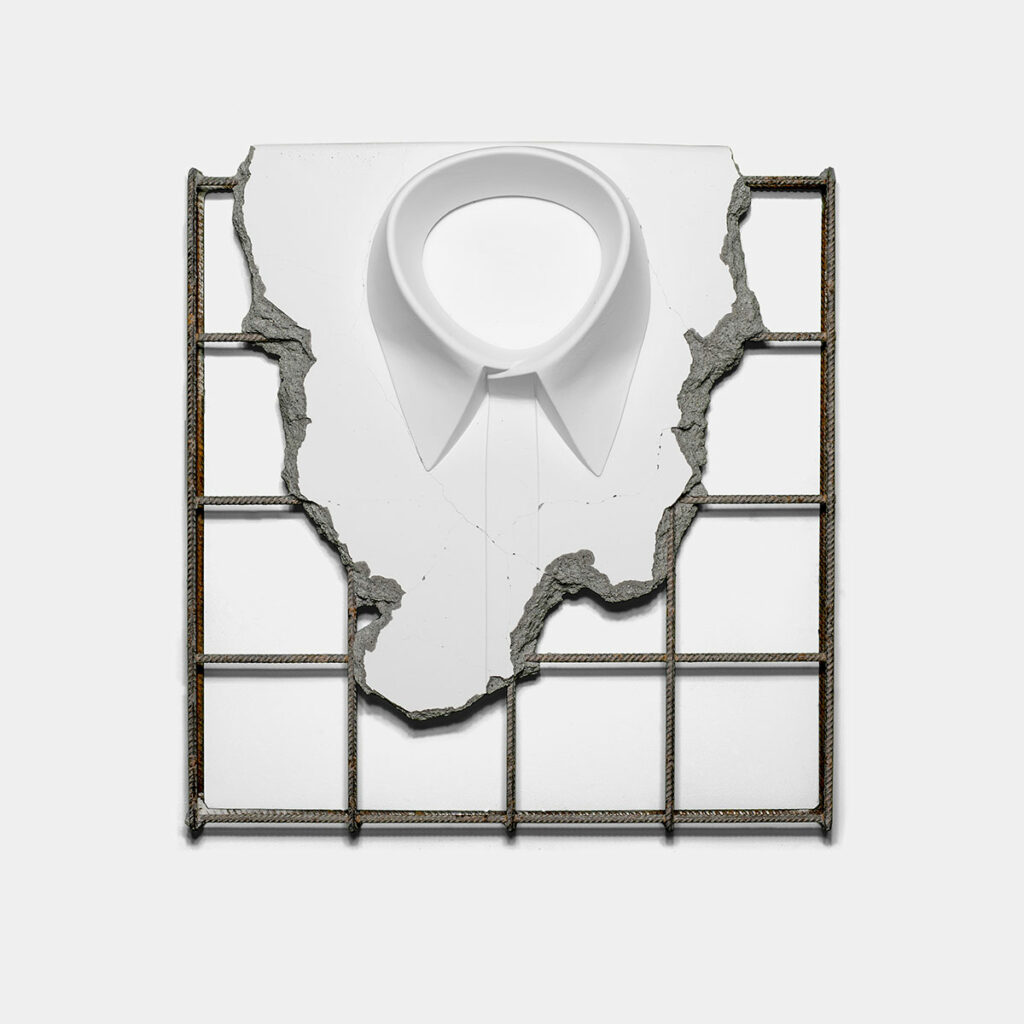

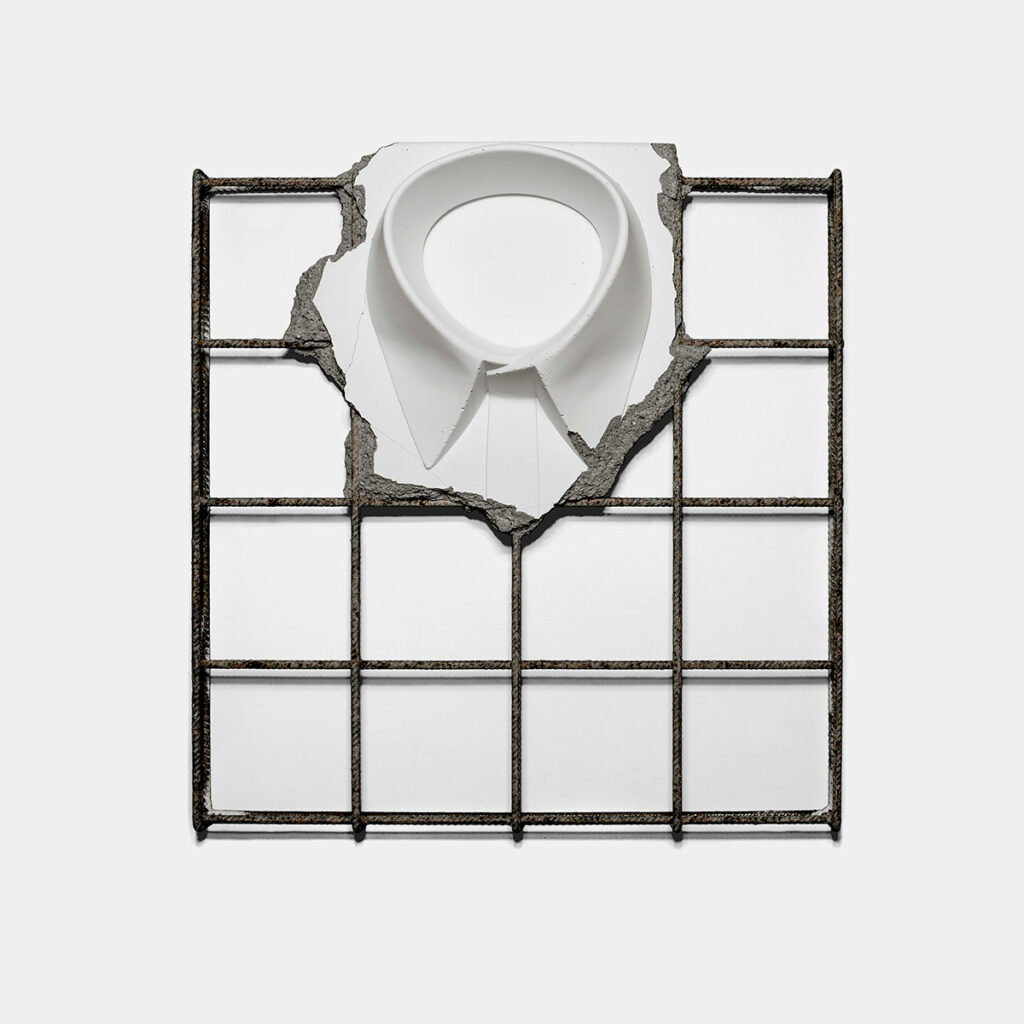

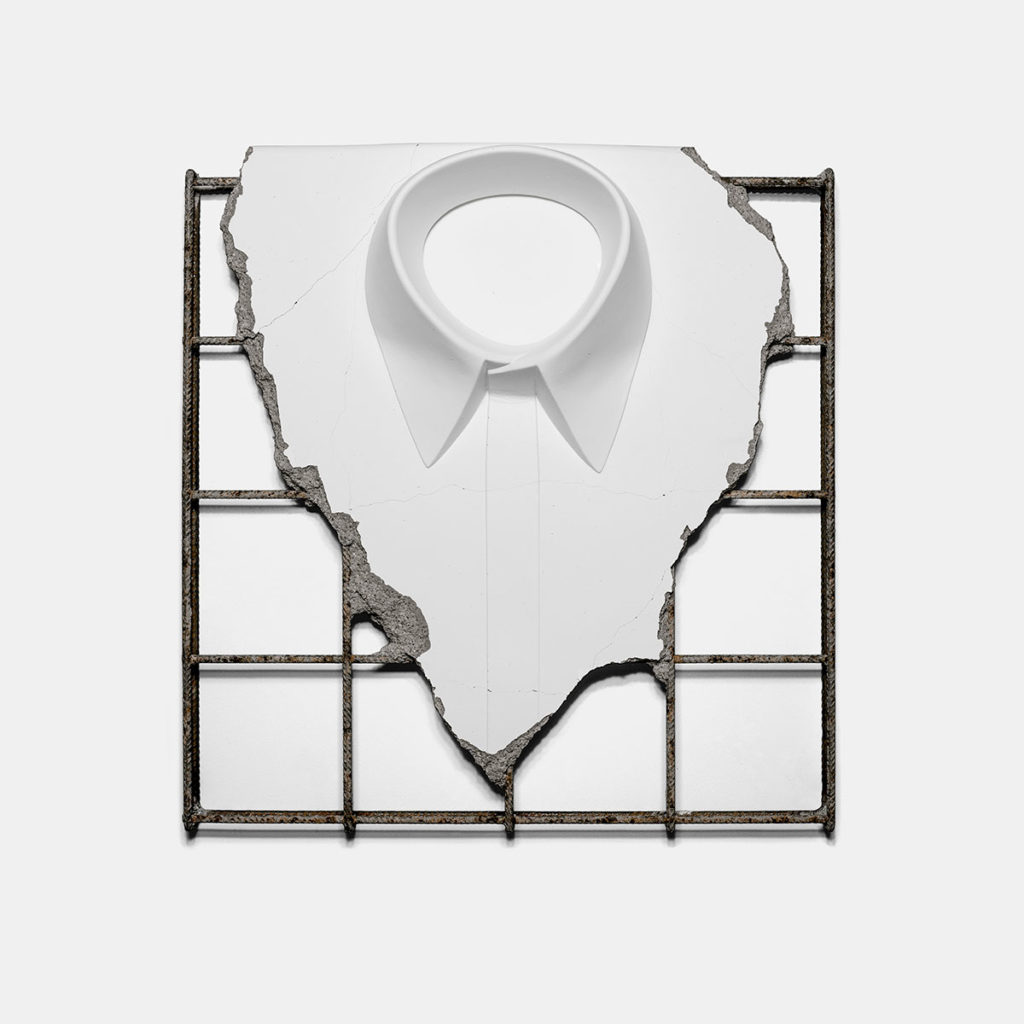

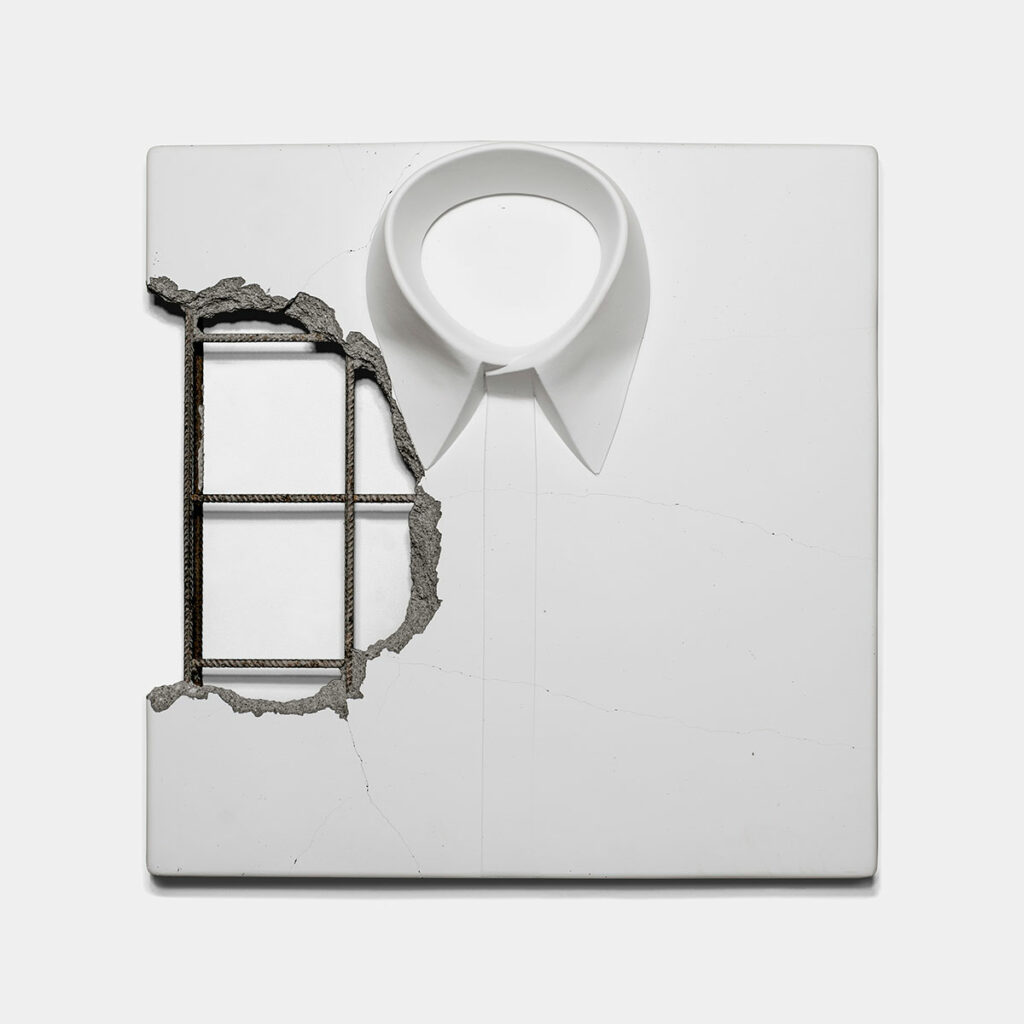

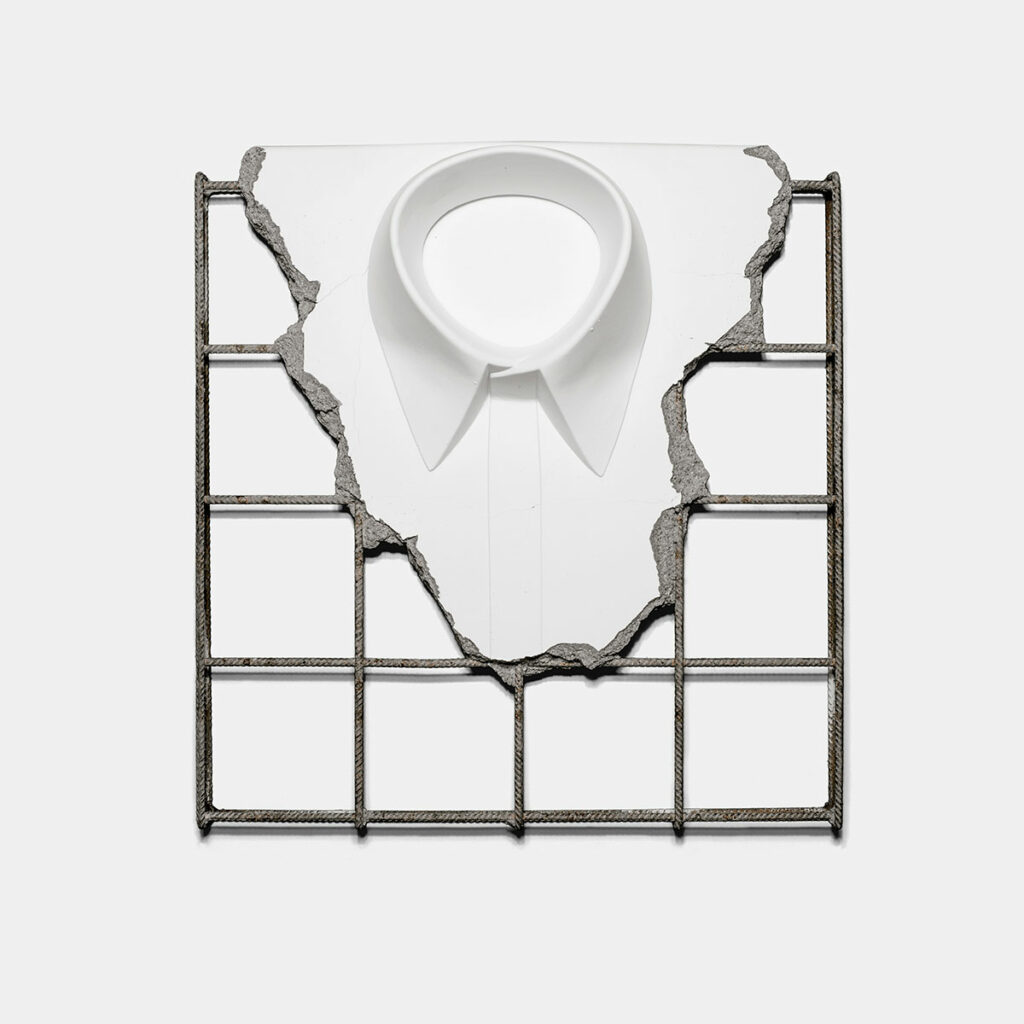

These concrete sculptures are formally synthetic versions of their real-life model: a white square shape measuring roughly 45,5 cm per side, a vertical strip that suggests the front row of buttons and a precisely rendered collar. Everything has an austere whiteness, indicative of the neatness and exactness this piece of clothing is supposed to bring to the one who wears it. The model used for the sculptures is usually associated with a more formal (largely) masculine look: the white shirt with a white collar. Such is the term the artist has chosen to name this series, putting to use, in a way that is structural to his artistic practice, an idiom or cliché, such as “white collar”, which is defined by the online Portuguese language dictionary Priberam as a descriptive for a “person who works in management or administration, in positions that do not entail physical work, and from whom a certain degree of formality in dress is required”. More recently, the artist has created another piece, a sculpture entitled “Branco Sujo” [Dirty White] (2016), using the same basic form as the previous one, but now on cast bronze. The adjective “dirty” combined with the image of the white-collar shirt conveys a critical stance regarding the subject and its various correlations.

In 2021, I wrote a text about his 2020 piece, “Produção Caseira” [Home-made], in which I mentioned another work of his, “Vendo País para comprar casa” [I wish to sell my Country to buy a house] (2019), in which “a critical and satirical play on economic values” is quite present, thus taking a reactive stance while drawing attention to the levels of social injustice and inequality that affect us all to some degree, but which we simultaneously accept as an assumption that is part of the status quo of our everyday life. “Vendo País para comprar casa” consists of twenty-eight marble plaques, engraved in low-relief as though they were tombstones: in each one of them is written an economic link between horizontal property and the price of a stay at a hotel, as well as a depreciated evaluation of mortgage value. These instances provide just a few possible reference points for situating Isaque Pinheiro’s artistic practice in formal and conceptual terms, as reflected in “A Malha” [The Mesh], a piece that is exposed to the public view on this gallery’s façade. “A Malha” is a large, composite work whose first stage of production took place in an industrial complex, using a mould created by the artist that is based on the 2008 sculpture “Colarinhos Brancos”, but with a substantial difference: it is now a series of individual sculptures, each of them finished by the artist himself, which come together in the gallery’s front as an architectural relief that at first glance may resemble a modernist mural. However, a more careful look at the piece reveals that this mural is like a sequence of figures inscribed into each element of the installation marked by the white-collar shape, essentially by means of the violent action that strips away the corporeality of each one of those elements. In this manner, “A Malha” is also an expressive strategy that the artist employs to disrupt our certainties concerning what we see and how we see.

One of this work’s defining features is a change in texture and volumetry that lends it a certain degree of movement, taking into consideration its geometrically precise grid. At a first glance, its title may refer to the mesh of the orthogonal grid that defines the installation’s set-up, and at a second one to something that is not immediately visible: the iron mesh that emerged after each sculpture had been hammered out, stripping away, as previously mentioned, the internal structure of each piece. In this physical action, Pinheiro defines a relation between the gesture and the word that, besides describing the gesture as both process and result, also includes the polysemy of the vocable and its condition of possibility as a linguistic process. In this manner, the artist develops a differentiation on the formal observation of the work, making it in part a factual, objective observation of the construction of this work through one word: the mesh. However, on another level, this piece reactivates a critical assumption that is not immediately recognisable, by connecting each white-collar figure with a list of judicial proceedings that the general public may consult upon request. In other words, each sculptural element is associated with the number or description that identifies each one of those proceedings. That listing can only be consulted together with the list of the works that make up the whole exhibition.

Let us now return to 2008’s “Colarinhos Brancos”, in order to understand a correlation of relationships that are more coherently developed in “A Malha”, in all their critical and political complexity, and in a variety of generic forms that are usually common knowledge, like the notion of “white-collar crime”, a term that is also part of juridical parlance, as can be seen in the definition below, one of many possible ones: “The concept of white-collar crime became widely known through Sutherland’s work, during the late 1930s. The rich and powerful had been engaging in criminal pursuits long before that; however, there was little perception of such behaviours, because the dominant view was that criminality was associated with poverty and all the other factors linked to this unfavourable financial condition”.

This project by Isaque Pinheiro is indicative of a continued concern with social and material issues of the society in which we live; these issues have influenced his work, namely in terms of the return to large-scale works that exist in the public space, as well as of the use of language and other semantic and statistic devices. On the other hand, the installation on the gallery’s façade confronts us with an ambiguous and paradoxical stance, in the sense that each one of these sculptures is evocative of the presence of a body, intensifying the public exposure of the white collar’s symbolic figure, which, though it may perhaps not be immediately associated to dubious social conduct, still has a symbolic grip on our collective memory. Regarding this, Pinheiro defines a double play, somewhere between satire and criticism, confronting some social conventions, which are often generalist and based on falsehoods, prejudices and ignorance, with certain offences that are often the target of a seemingly defamatory logic in which material evidence is hard to discern, and thus almost invisible, as is the case with the listing that, though associated to the installation on the façade, demands a specific request to be consulted.

In Isaque Pinheiro’s oeuvre, a language is an essential tool in terms of the use of metaphor, or even hyperbole, as a figure of speech that is associated with a form and transcription of reality that is not always readily comprehensible.

João Silvério

1 “Colarinho-branco”, Dicionário Priberam da Língua Portuguesa [online], 2008-2021, https://dicionario.priberam.org/colarinho-branco

2 Cf. Bruna Hernandez Borges, “Os Crimes de Colarinho Branco e as (des)vantagens da Justiça Restaurativa”, Master’s Degree Dissertation in Criminal Law, University of Coimbra, 2017, p. 14.