overview

05 November – 17 December 2022

“e… o lixo vai?!”

António Ole

Curated by Inês Valle

An artist from his time, but always looking forward!

by Inês Valle, 2022

As I walk, I write the words of a journey bigger than my own.

The journey of an artist that spans over 50 years has been revealed in the intimate layers of his art on complex issues of people, stories and struggles of mutating societies. António Ole, from Caluanda, has become one of Angola’s most recognised conceptual artists in recent history, which has led to a strong rethinking of contemporary art in the African continent.

In a brief contextualisation of the landscape in which António Ole’s work takes place, it is worth recalling some social, cultural and political moments that started in the twentieth century and had significant repercussions in Africa. The first movement for the valorisation of Black Culture appeared in the USA with the Harlem Renaissance (1918), which had close involvement in organisations related to Civil Rights and Reform. Followed by others such as Pan-Africanism, Pan-Arabism, the Black Arts Movement, the Black Panther Party, Black Feminism, and even the controversial Afro-French-Caribbean Negritude movement, all of which contributed towards notions of representation and definition of Black identity.

An epoch of effervescent change, one which Angela Davis described as: I wanna be there. This is earth-shaking. This is change. I wanna be a part of that 1 As one might expect, these ideals were also reflected in the field of the arts, with events that valued African culture and its diaspora, such as the first African festivals – The FESMAN (Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres, Dakar, 1966) and the FESTAC (Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, Lagos, 1977).

The second took as its symbol the famous mask of Queen Idia reproduced by Erhabor Emokpae, one of Nigeria’s pioneers of modern art 2. FESTAC, which Antonio Ole documented in one of his films, counted with the presence of more than 17.000 participants from 50 countries and was regarded, until that date, as the largest cultural event ever held in the African continent. Yet, Angola and Portugal lived for decades in a vacuum of isolation. It was only after 25 April 1974 that they progressively became aware of the new world situation – in Angola, freedom and detachment from the values imposed by Colonialism were imperative. Later on, in 1989, the polemic contemporary art exhibition Magiciens de la Terre opened at the Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villette, shaking the structure of Eurocentric art history. A group exhibition in which 50% of the artists were “non-Western” and some had no formal education, some of whom are now a reference in Contemporary Art History, such as Chéri Samba, Twins Seven Seven and Esther Mahlangu.

It is on against a backdrop steeped in political and cultural stimuli that the artist António Ole witnesses his country in conflict for more than three decades, from the nation’s struggle for decolonisation, through the consolidation period of independence, to an easing when the Civil War came to an end in 2002. Despite the adversities of an unstable country which until its independence had one of the highest illiteracy rates in the world at 85% 3, Ole, was blessed with the privilege of having access to education and later travelling. Having access to Marxist doctrines and books forbidden by the dictatorial regime, he acquired a comprehensive perspective that enabled him to expand his experiences across different geographies and mentalities, which allowed him to develop a critical attitude and reconsider conventional notions about Portugal, Angola, Africa and the world.

Africa and the world.

In the midst of these voices, which echoed desires for change, at the beginning of his career, he presented works of an ironic and sarcastic nature that exposed socio-political themes that were sharply critical of that time’s society. However, ambiguity was not always well received, and some of his works were censored and banned from being exhibited – which was the case of “Sobre o Consumo da Pílula” , an artwork shown and awarded a prize at the IV Salão de Arte Moderna de Luanda in 1970. A gouache did when the artist was only nineteen years old. An artwork with strong influences of both the Pop Art movement and Comics, which the National Feminine Movement banned by putting pressure on the governor-general of the colony to restrict its exhibition because it portrayed Pope Paul VI (1897-1978) taking the pill (artwork number 8 in the show). Similarly, the feature documentary on the music group involved in the clandestine anti-colonial struggle ‘O Ritmo do N’Gola Ritmos’ (1978) was ‘suspended’ for 11 years because it referred to the role of Liceu Vieira Dias, a sympathiser of the MPLA’s ‘Active Revolt’. However, despite Ole’s acknowledgement in an interview with Barbara Murray in Zimbabwe that his 1970s works had a more political nature, he explicitly rejects engaging politics in art 4. António Ole has always been driven by his integrity and his urge to call for freedom, refusing any political office or benefits from whatever regimes – always a humanist, but never a cacique – which has until today granted him a sense of freedom and independence to which his work is an unquestionable witness.

The question e… o lixo vai?! that gives title to his solo exhibition at the .insofar gallery denouncing precisely his creative freedom. If, on the one hand, it alludes to one of the expressions he repeatedly heard from people who perplexedly observed him collecting `trash’ and making artworks with them, on the other hand, it refers to the variety of materials discarded by the city, which he uses, such as used and rusty iron sheets, bones, shells, saltpetre, red earth worm-eaten wood and even peeling paint from walls – taken as “metaphorical” materials to address themes dealing with actual memories of war, poverty, slavery, destruction, that are the Angolan people’s daily struggle, and which he has always centred its practice 5, as is perceptible in this exhibition. Here, I can refer to “(un)Discardable Memories”, an installation developed during the “Hidden Pages, Stolen Bodies” project, which deals with the theme of slavery and forced labour associated with the colonial violence that transforms the bodies of enslaved people into a commodity: stolen lives and bodies6. An installation made from used burlap sacks and a line of four sculptures made of rust-corroded metal dishes that perilously stand as trophies on a wooden shelf, encouraging to rethink time through a reverse gaze, metaphorically evoking Angolans’ long and precarious history, powerless to claim their freedoms. As for “Mural do Maculusso”, which takes its name from his neighbourhood in the city of Luanda, which emerged as a musseque during the Portuguese colonisation period and today is one of the city’s epicentres. A place which, similarly to his work, agglomerates the traces of time. A sort of patchwork of his various artistic phases, in which, in recycling, superimposing and rebusing, an enormous collage emerges (composed of fabrics, newspaper and magazine clippings, posters, photographs of the city and even references to his earlier works, such as the black and white portrait of a woman in his series “Mens Momentanea (I)” of 1973).

In this cartography of the places where he lives and influences him to communicate ideas within time and space, Ole sets “things against each other”, gradually building a sociocultural archive of unparalleled interconnections.

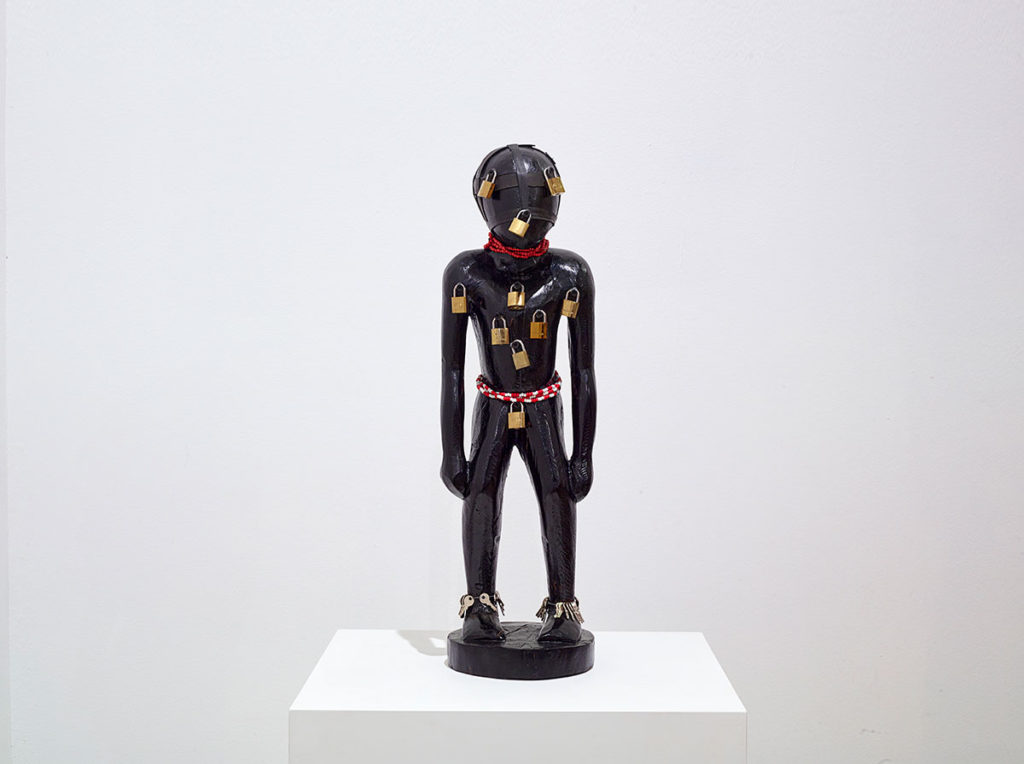

The triptych “Urban Choices II”, for example, captures everyday scenes in Luanda, at the São Paulo Market, depicting life in a contemporary African city, portrayed by urban and religious objects piled up in towers or categorically lined up in a blending of utilitarian objects by colour, shape and function, like the ones we find at an informal market stall. In a different market, also in Luanda, he acquired a traditional wooden sculpture with which he created the artwork “Corpo Fechado” (The Closed Body)–described by Ana Balona Oliveira as a sculpture that carries the protective evocation to contemporary times, sealing it from the energies of war, disease, greed, envy, corruption, as well as the evil eye 7, revealing both his spiritual sensibility, ethnographic and traditional knowledge of Angolan and African culture.

His interest in marginal and marginalised realities – in the remains of a society under construction (…) has led him to produce portraits, study the forgotten everyday heroes, map unexpected constructions, and investigate a collective sense of suffering that is so often silenced in the name of deletion of memory as a possible form of catharsis 8, as Miguel von Hafe Perez characterises him.Thus, amidst his vast and eclectic oeuvre – painting, sculpture, collage, drawing, installation, photography and cinema – the one that António Ole considers one of his most important artworks since it represents a symbol of his artistic development, combining found objects and bright colours, in a pop art style 9 is the “ township walls” series, developed between 1994 and 2004. A series comprising several installations focusing on the architecture and life in the musseques of Luanda – those African shanty towns overflowing with people and vitality on the outskirts of the concrete city so dear to António Ole 10, as José Fernandes Dias describes in 1995. In this exhibition is included the iconic “Township Wall (X)” created for the itinerant collective exhibition Africa Remix – Contemporary Art of a Continent” (2004) curated by Simon Njami11, and later included in his retrospective António Ole: Luanda, Los Angeles, Lisbon (2016) at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, co-curated by Isabel Carlos and Rita Fabiana.

Today, it extends over nine metres along one of the walls at .insofar gallery.

This presence of walls, or vestiges of them, is also incorporated in other series of the artist, such as when he poetically creates works by appropriating paint peels that were used to coat buildings in Luanda. Like the artwork, “Quick drawing III” where I recall Delfim Sardo’s words: walls are skins that hold in their wrinkles the memory of all that happens to a city 12. These skins lingering over the poetics of urban archaeology draw us into every detail unveiled by his work that borrows from personal and collective daily lives.

The painting “Desintegrações I” is another strong example. Produced at the end of the Angolan Civil War and bearing the memories of one of the most emblematic buildings of the culture of his city – the Elinga Theatre, a “building which most symbolises a way of being and living in Luanda… Walls [where] one breathes time”13 reflected Marta Lança, among the numerous threats of destruction to this national monument. Hence, by reusing an awning from the theatre’s exterior advertising, which was deteriorating to bits, António Ole has created a work where he cuts, paints and transforms the memory of time and, like an omen, announces the end or the beginning of an era.

The work of António Ole is not solely about the city. The sea, the water, the countryside, the earth and the immaterial also wander in his soul. Frequently hiking along the sands of the island of Mussulo, where he gathers objects that the ocean presented to him, allowing himself to be imbued into the vast landscapes of luminous horizons.

The paintings A Ténue Luz do Ouro” (The Dim Light of Gold) and “O Poder da Água e das Partículas Sensíveis” (The Power of Water and the Sensitive Particles), separated by thirty years, could somehow be interconnected by the liquidity of their forms in oneiric scenarios. The first takes us into a spiritual, mythological or ancestral world in which humanoid and animal figures flutter through the transparencies of light. The second, in a 50 watercolour panel, depicts landscapes of skies and seas. Perhaps liquid memoirs drawn from his many voyages to the islands in Africa: Mussulo Island, Cape Verde, Gorée, São Tomé, Robben Island, Mozambique Island, Zanzibar, Lamu and Réunion. Works that testify his interest in spirituality, in profound subjects that slowly are fading away from African societies, particularly in the urban centres where the violence of external influences weaves other values.

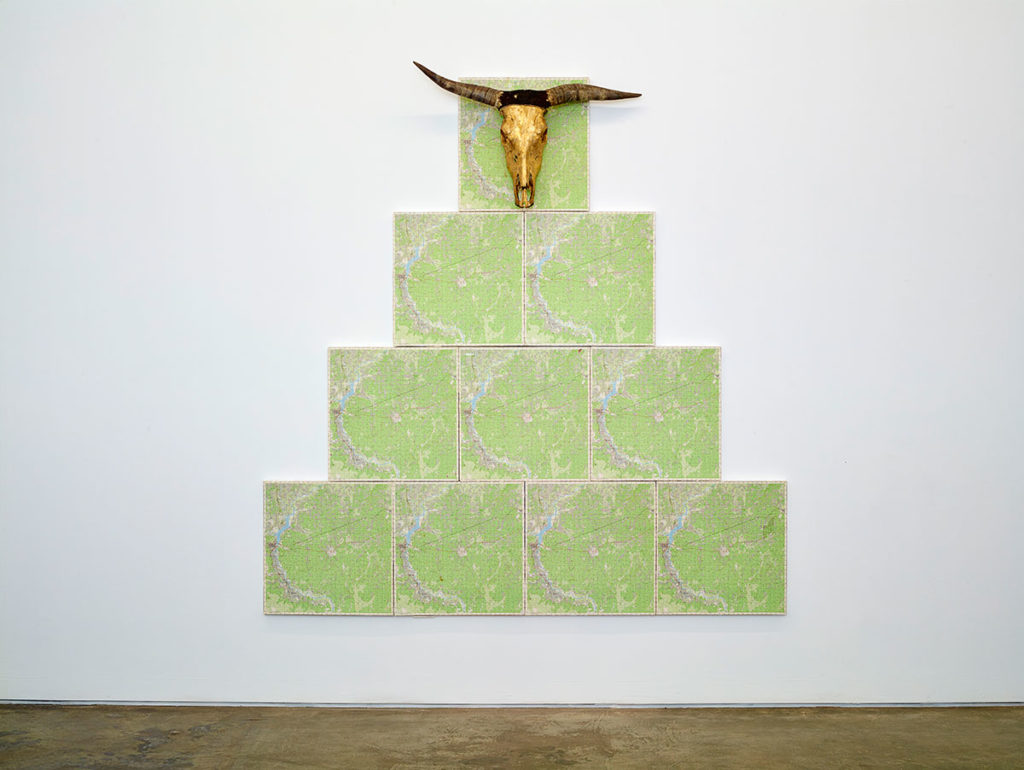

In another work in this exhibition, Ole tackles current environmental and economic issues, using elements from the natural world to warn us of irreparable losses in pursuit of economic progress. I refer to “Boi Sagrado I – à memória de Ruy Duarte de Carvalho” (Sacred Ox I – in memory of Ruy Duarte de Carvalho), a work that embodies multiple meanings. Taking this as a starting point, the film “Ondyelwa: Festival of the Sacred Ox” (1978), directed by his close anthropologist friend, captures in his documentary the sacred ox procession – a ritual practised by the Nyaneka-Humbe.

If on the one side, António Ole warns us that climate change has been worsening, causing longer drought cycles 14, with severe consequences for the entire ecosystem, such as the drying up of rivers, extinction of wildlife, forced migrations, biodiversity loss and even soil erosion, highlighting the particular case of Namibe, where, notwithstanding the adoption by the Angolan government in 2016 of measures to mitigate the effects of the drought, over a million Angolans continue to be affected, and if we further associate these facts to oil exploration that is booming throughout the territory, in an atypical economy, such as that of Angola where oil represents 70% of its revenue15, the artist, on the other hand, challenges us to reflect on alternative economies for his country, such as farming and cattle breeding, as a way of simultaneously perpetuating not only the natural ecosystem but also to value local identity, wisdom, culture and economic independence.

Thus, perhaps the ox head covered in golden leaf, which stares at us from the top of the Cunene River map in Namibe, will make us ponder on the delicate balance of tradition and progress.

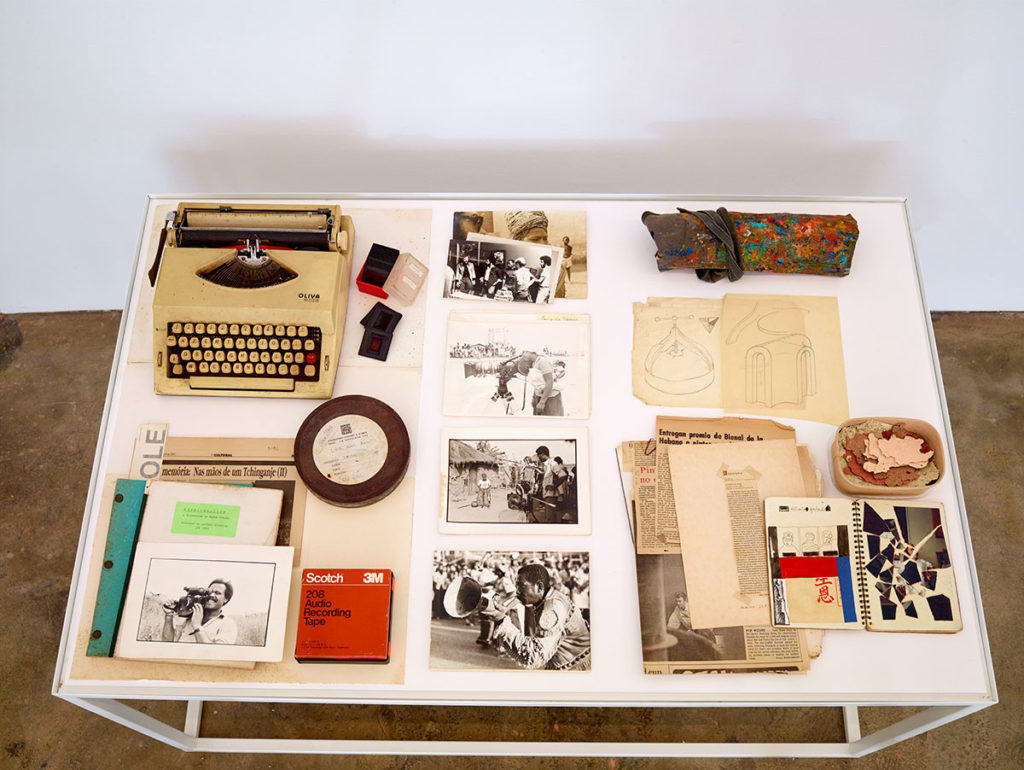

Finally, the vitrine.

An archaeological memory of the long and eclectic career of António Ole, never publicly shown, is now revealed through the simple unveiling of objects soaked with stories, preliminary documents, notebooks filled with drawings and ideas, sketches of canvases on tracing paper, his Oliva 2002 typewriter, film scripts, films and audio reels, his thickly-painted atelier apron, numerous newspaper clippings of reviews and interviews, and old black and white photographs of the years he spent documenting his country, all of which were categorically preserved.

These photographs, taken by António Ole, are records of the shooting scenes from his four emblematic films – Conceição Tchiambula, a day, a life (1982); O Ritmo do N’Gola Ritmos (1970); O Caminho das Estrelas (1980) and Carnaval da Vitória (1978), a time when he also worked for TPA (Angolan Popular Television) documenting the country. António Ole’s perspective, as well as that of other African filmmakers, namely Paulin S. Vieyra, states that this was a crucial period in our history nobody ever taught it to us at school, we only know it by hearsay, by tales, by legends, by storytellers, and, so it was fundamental for us to return to our origins16 and if we did not have filmed [Angola] I believe the memory of this period would have been lost 17. Thus, the importance of these films goes far beyond showing the political and social transformation of the African continent. Rather they also offer a refounded view of the stereotypical perspective that [still] prevails in Africa. As Wole Soyinka alerts us in his book of essays Myth, Literature and the African World of 1975, in such a wider world of myths, stories and mores; in such a total context, the African world, like any other ‘world’, is unique.

This exhibition contributes towards a comprehension of the work of master António Ole, which provocatively shivers us from the inside of how honest it is.

References:

(1) Interview with Angela Davis in “Free Angela and All Political Prisoners”, a documentary by Shola Lynch, 2012. (2) Erhabor Ogieva Emokpae (1934-1984) was a Nigerian artist recognised as one of the pioneers of Modern Art in Nigeria. His famous bronze replica of the ivory mask of Queen Idia served as the official symbol of the Second World Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). This 16th-century mask belonged to the Benin Empire, which was looted by the British from the Palace of Benin’s Oba during the Benin Expedition in 1897, and currently is held at the African Section of the British Museum. (3) Liberato, Ermelinda. “Avanços e retrocessos da educação em Angola”, University Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola. Published in Revista Brasileira de Educação v. 19 n.59, 2014. (4) Murray, Barbara. Gallery magazine, Zimbabwe, June 1998. (5) Valle, Inês. “Uma calunga de esperanças sem fim – anotações sobre António Ole”, exhibition catalogue, Lisbon, 2011. (6) Fabiana, Rita. “Insula ou o Corpo de Obra”, exhibition catalogue, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2016. (7) Oliveira, Ana Balona. “The Vital Matters of António Ole”, exhibition catalogue at Movarte gallery, 2021. (8) Perez, Miguel von Hafe. “Between the blue earth and the brown sea”, exhibition catalogue, Sala 117, 2016. (9) Siegert, Nandine. “The Beauty of Elusive Architecture”, exhibition review, “In the Skin of the City”, Buala, 2010. (10) Dias, José Fernandes. exhibition catalogue, Delphina Studio, London, 1995. (11) The touring exhibition “Africa Remix – Contemporary Art of a Continent” was shown at Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf, 2004; Hayward Gallery, London, 2005; Centre George Pompidou, Paris, 2005; Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2006; Modern Museet, Stockholm, 2007; Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2007. (12) Sardo, Delfim. “A pele das Paredes de António Ole”, exhibition catalogue “Na Pele da Cidade”, Luanda, 2008. (13) Lança, Marta. “Elinga, an affective heritage”, Rede Angola, 2014. (14) Report: “The history of recent droughts in Africa” (1980-2020), University of Gothenburg & Jennifer Nnopuechi, 2021. (15) Angola – Market Overview, 2022. (www.trade.gov) (16) Vieyra, Paulin Soumanou (Benin, 1925-1987), “Le cinéma au Sénégal”, Editions OCIC/L’Harmattan, p. 152, 1983. (17) António Ole, “O Angolano de Múltiplos Talentos”. (www.dw.com)