Like lost souls, they wandered in the darkness of shadows, frightening the Portuguese troops until their retreat. In these two paintings, Marcela evokes two fragments or events from the same historical period. In one, there is a representation resembling a premonition of the downfall of the Portuguese Empire in Brazil, where “phantasmagoric” women surround a fallen soldier. On the other, we have the inevitable fate of July 2, 1823, the moment of victory for the people of Bahia. In the foreground of this painting, the women of Saubara rejoice in triumph in a clearing, while in the background, dark shadows represent Portuguese soldiers fleeing through a tunnel or cave. These symbol-laden and mystical works transport us to past times that become increasingly present when we reflect on the identity of a people, incorporating both historical and contemporary elements. For instance, when Marcela pays tribute to historical figures by personifying three female warriors from Brazilian history—Maria Quitéria (1792–1853), Joana Angélica (1761–1822), and Maria Felipa (?–1873) —or when she paints a “plainclothes” Portuguese soldier wearing contemporary attire, a t-shirt adorned with a burning caravel print. The burning caravel can symbolize the destruction of the colonizing and exploitative ships that marked the beginning of colonialism, but it also carries a powerful message of questioning the legacies of the past or even the power structures and oppression that still persist in contemporary society.

In contrast to historical representations, Marcela Cantuária propels us into an imaginary and magical world through vibrant colours, a space inhabited by mutant beings, beasts, and anthropomorphic monsters that the artist richly uses to reconstruct the complex narrative of history. These fantastic elements allude to the magical and imaginative side that all stories of struggle carry, adding a layer of depth and evoking the viewer’s imagination. References to the minor arcana of the tarot, which play a significant role in the artworks, stand out. They are depicted in the four corners of the painting, bringing a symbolic and mysterious dimension to the narrative. Additionally, the presence of the tricephalic eagle carrying a soul or the sardine-women with the heads of Bahian heroines and bodies of Portuguese sardines hovering over the painting’s narrative. These symbolic references add layers of meaning and invite the viewer to delve into a deeper interpretation of Marcela’s work, exploring the mysteries and multiple senses that each element carries.

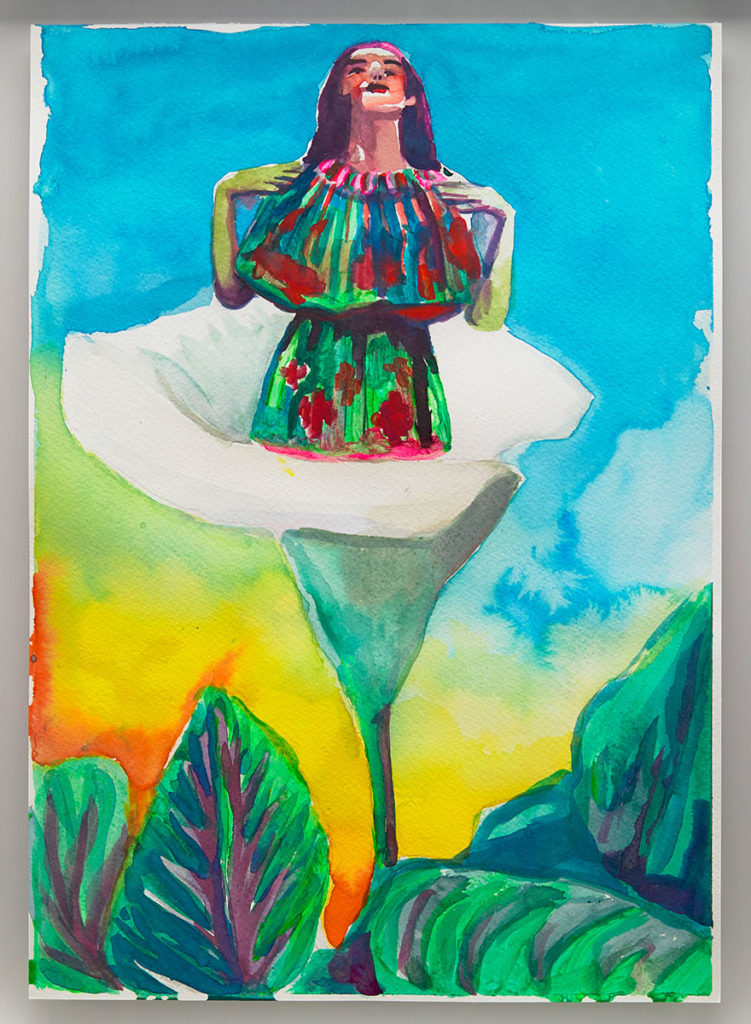

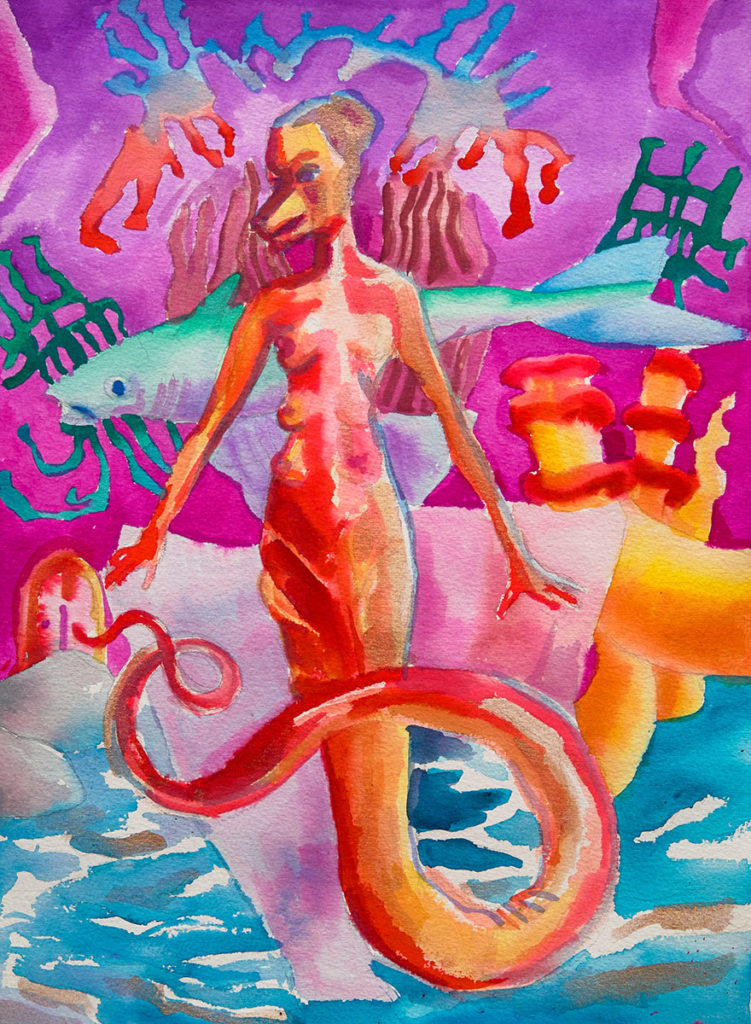

In dialogue with these two works, the artist expands the universe of the depicted history through smaller-size works such as watercolours and sculptures, seamlessly blending reality with the imaginary and natural world. An example of this is the representation of the eleven-headed dragon in flames, where each head portrays a man who navigated, explored, or colonized Brazil. In another painting, we encounter the woman-snail, depicted as the warrior and protector who, with every step, raises her humanoid arrow aiming for the freedom of the indigenous, caboclo, or enslaved African people.

It is fascinating to think about how the words and message of the great Italian Baroque master Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1656), expressed in her 1649 letter, can echo and find resonance in different times and places. While it is impossible to say for certain whether Artemisia could have imagined that her words would have a lasting impact on another continent and in a later period, it is undeniable that her struggle and determination have left a mark on the history of art. Could she have imagined that her words would echo or leave a profound message that Marcela Cantuária brings to us now, two centuries later?

The exhibition space, punctuated by these works, is also an oneiric realm—a palace from the 18th century commissioned by D. Pedro de Bragança, the first Duke of Lafões and an illegitimate descendant of King D. Pedro II. After being denied the throne, he hired the most prominent artists of his time to create a place to allow the soul to take flight as it wished. Thus, at the Palácio do Grilo, it is possible to simultaneously witness the dreams of a renegade man and the vision of an unconformed woman. This duality of perspectives provides us with a performative experience that transcends transatlantic borders, connecting different universes and narratives, in some way doing justice to the ambition of Julien Labrousse, the current owner of the palace.

Lastly, the artwork “Serpentária” is a striking piece in the exhibition. It is an oratory inhabited by a chimaera, a hybrid figure combining the characteristics of a woman, a serpent, and a she-wolf. This figure can be interpreted as an oracle, an entity that possesses transcendental knowledge and wisdom. The sanctuary-museum where this chimaera resides is a sacred space, adorned with a mirror that reflects and multiplies both the presence of the chimaera and the numerous micro-paintings of metamorphic beings, creating a mystical environment. Simultaneously, as she opens the doors to her sanctuary, we are invited into a world of transformation and self-discovery, where she becomes a guide to help us explore the central themes of the exhibition: struggle, freedom and independence.